Published April 30, 2023

(U.S. Embassy in France)

Introduction

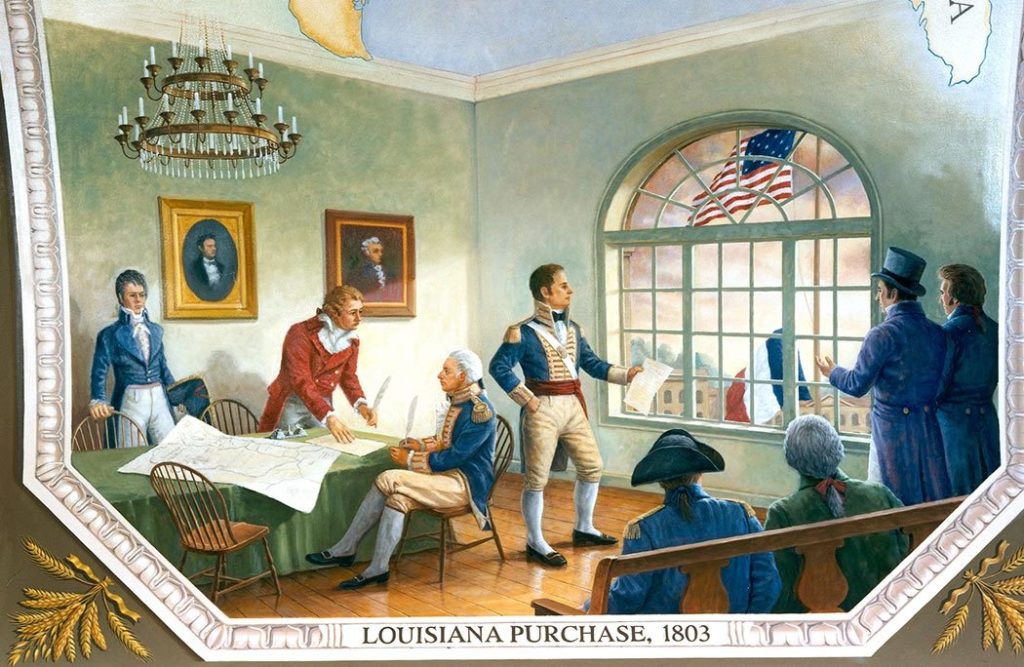

The Louisiana Purchase, concluded on April 30, 1803, is one of the most important events in the life of the United States.1 It allowed American expansion westwards and led to the acquisition of a territory which covered, entirely or partially, present-day Louisiana, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Colorado, Kansas, Missouri, Iowa, Nebraska, Wyoming, the Dakotas, Minnesota, and Montana. One might wonder why France, then a strong power led by Napoleon Bonaparte, would sell such a huge territory to a young nation which at the time was not even 30 years old.

This short article concludes that France sold Louisiana for three reasons: losing Saint-Domingue; anticipating the next war with the United Kingdom; and turning the United States into a rival of the British.

The Loss of Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) was a French Caribbean colony designed to be the centerpiece of a French colonial empire in the Americas.2 The “Perle des Antilles” (Pearl of the Antilles) was by far the most profitable colony, thanks to its massive exports of goods such as coffee, cotton, and indigo. However, it was sugar which made it so profitable. From the 1770s onwards, it was the largest producer of sugar in the world.3 The weight of the colony in the French commercial balance was considerable. The exports of “colonial goods” (except for cacao) from Saint-Domingue made up for more than 80% of the entire French colonial trade before 1789, and in the early 1790s its produce accounted for 40% of all the French overseas trade.4

As an illustration of its enormous economic power, in 1788, the colony alone exported goods totaling a value of almost 176 million livres tournois, which was more than the value of British exports from Jamaica, Barbados, Granada, Saint Vincent, Dominica, Saint Christopher, Antigua, Montserrat, and the Virgin Islands combined (a bit more than 157 million livres tournois). It was also about four times the value of exports from the neighboring French colonies of Martinique, Guadeloupe, Tabago (Tobago), and Guyana combined.5 In the early 1790s, its produce was bigger than all of Europe’s other Caribbean and American colonies combined and was the source of 40 and 60% of the European consumption of sugar and coffee respectively.6

Therefore, Saint-Domingue was undoubtedly the most important French colony in the Americas. The Pearl of the Antilles and Louisiana were meant to constitute a strategically harmonious couple: the former was considered essential to develop Louisiana, while the latter would serve as a “colony of support” and provide supplies, livestock, and wood to Saint-Domingue.7

However, in the 1790s, a rebellion developed in the colony.8 Following news of the French Revolution, whose Republican ideals made freedom a very real possibility, a slave revolt led mainly by Toussaint Louverture occurred on the western part of Hispaniola (the island where Saint-Domingue was located).9 Napoleon, who wanted to create a French colonial empire in the Americas in which Saint-Domingue was to play an essential role, had to reassert control.10 The revolt had naturally impacted trade; by 1801, sugar exports were only 13% of their 1789 total.11 The expedition to stop the rebellion (February 1802-November 1803) was a disaster; the French soldiers failed to control the colony, having to face the rebels, yellow fever, and a British blockade.12

(Polish Army Museum, Wikimedia)

As a matter of fact, even before the complete defeat of the expedition, Napoleon had decided to sell Louisiana to the United States. The inability to retake control of Saint-Domingue ended Napoleon’s vision of a French colonial empire in the Americas.13

The Prospect of War with the United Kingdom

But it was not merely the loss of Saint-Domingue that triggered the sale. A serious threat was looming: the very likely prospect of another conflict with the United Kingdom. While both countries had concluded a peace treaty at Amiens in March 1802, it had not been the result of reconciliation, but rather of exhaustion.14 Despite the peacetime, both countries remained distrustful and defiant. The peace was described by King George III as “experimental.”15 Furthermore, since the United Kingdom gained so little from the settlement, London’s commitment to peace was correspondingly weak.16

A key issue was that the British were convinced that Napoleon’s “inordinate ambition,” from the words of Foreign Secretary Lord Hawkesbury, was a permanent threat.17 Specifically, the peace treaty had ignored many of the fundamental problems troubling London, notably French control of the mouths of the Scheldt and the Rhine, and France’s continental dominance.18 Furthermore, the settlement failed to substantially improve the British economic situation or to re-open the French markets because of Napoleon’s protectionist policies.19 More importantly, France acted in a way which alarmed British officials, such as its navy’s energetic and large-scale reconstruction, its annexations of European territories, or its ambitions in the Middle East. Such acts were considered a violation of the spirit of Amiens.20

Although France had not breached the treaty, its considered-hostile actions led the United Kingdom to violate the peace of Amiens; the British had still not left Pondicherry despite the fact that all French colonies were to be returned under Article III of the treaty. They had also apparently omitted to order their troops to evacuate Alexandria, and Malta was still under British occupation three months after the ratification of the treaty, in contradiction of Article X.21 As a matter of fact, on February 9, 1803, London announced a halt to all withdrawals until France had provided a “satisfactory explanation” for its actions, which Napoleon failed to do.22 Negotiations between Paris and London increasingly turned sour, with the parties unable to reach an agreement.23

(histoire-image.org, Wikimedia)

It is in this general context that the sale of Louisiana must be considered. Tensions between the United Kingdom and France were increasing, and the start of a new conflict was gradually becoming a very real possibility. Napoleon was aware that without enough naval means to defend Louisiana, the colony would very likely be lost to the British in the event of war.24 British dominance at sea rendered the potential defense of the colony very difficult. Combined with the looming definitive loss of Saint-Domingue, Napoleon considered there was basically no reason to defend Louisiana. According to Public Treasury Minister François Barbé-Marbois (who would be in charge of the Louisiana Purchase negotiations on the French side, along with Exterior Relations Minister Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand), Napoleon stated that “[the British] have twenty ships in the Gulf of Mexico, they navigate those seas as sovereigns, while our affairs in Saint-Domingue worsen every day since the death of Leclerc. The conquest of Louisiana would be easy should they bother to descend on it.”25

Furthermore, it would have seemed imprudent to divert troops that could fight in Europe – the critical theater of operations – or in other relevant locations solely to defend Louisiana.26 While the vision of a grand French colonial empire in the Americas was surely promising, Louisiana was at the time little more than a vast, loose zone of influence that was barely exploited or even populated.27 Moreover, selling this seemingly undefendable territory would provide money that was needed for the war to come.28

After months of tensions, war would be declared by the United Kingdom on May 18, 1803, less than three weeks after the Louisiana Purchase was concluded with the United States.29

Keeping the United States on France’s Good Side

There is one final reason why France decided to sell Louisiana to the United States: to avoid antagonizing it and to attempt to turn it into a (naval) rival of the United Kingdom.

The United States had been unhappy about France possessing Louisiana once more. In 1762-1763, France, with the Treaty of Fontainebleau and the Treaty of Paris, had ceded Louisiana to Spain as part of the settlement of the Seven Years’ War, as compensation for the cession of Florida (encompassing the territory east of the Mississippi River up to Georgia, then controlled by Spain) to the United Kingdom.30 In 1800, however, France, having colonial ambitions, traded Louisiana back from Spain in exchange for Italian territory with the Treaty of San Ildefonso.31 As a result, the United States were to have a new neighbor; one which was well-known for its global ambitions and its potentially belligerent attitude, and which had pre-established links with the locals (the descendants of French colonists and Native Americans).32

And this frustrated the Americans. In 1795, they had obtained from Spain a right of free navigation on the Mississippi River to transport goods, with a right of storing such goods in New Orleans without paying a tax.33 This concession was deemed essential to protect American economic interests west of the Appalachian Mountains, and to ensure the survival of thousands of colonists who had settled in the Ohio Valley following independence.34 The renewed French possession, in American eyes, could threaten this: no deal to maintain such rights had been concluded with the French, and the American merchants could lose the position of dominance they had acquired in the region.35 And, obviously, the United States would now find itself blocked between two great powers.36

Furthermore, they believed that France could become a threat, unlike Spain. The latter was not feared by the United States, which assessed that Madrid did not have the military capability to prevent American expansion westwards. President Thomas Jefferson, in a letter to Minister to France Robert Livingston, perfectly summarized how and why the French presence was seen in a bad light, unlike the Spanish one: “There is on the globe one single spot, the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy. It is New Orleans, through which the produce of three eighths of our territory must pass to market, and from it’s fertility it will ere long yield more than half of our whole produce and contain more than half our inhabitants. France placing herself in that door assumes to us the attitude of defiance. Spain might have retained it quietly for years. Her pacific dispositions, her feeble state, would induce […] that her possession of the place would be hardly felt by us, and it would not perhaps be very long before some circumstance might arise which might make the cession of it to us […]. Not so can it ever be in the hands of France. The impetuosity of her temper, the energy and restlessness of her character, placed in a point of eternal friction with us […] render it impossible that France and the US. can continue long friends when they meet in so irritable a position. They as well as we must be blind if they do not see this; and we must be very improvident if we do not begin to make arrangements on that hypothesis.”37

Another testimony confirms and further details such a fear. According to French Colonial Prefect Pierre-Clément de Laussat (in charge of the regime transitions in Louisiana), American representative James Wilkinson (who would become the first governor of Louisiana) summarized the American concerns: they feared French ambitions and initiative; that the “adventurous” inhabitants of Louisiana would end up in confrontation with their neighbors; that the immense border would be a source of conflicts; and that France would plot “wars of division” among the American states eastwards.38

To settle this issue, James Monroe was sent to Paris to negotiate the purchase of New Orleans and its surroundings, or at the very least secure the same rights that the United States enjoyed during Spanish control.39 But Washington was willing to take a much stronger stance if need be. They threatened war and were ready to ally themselves with London if Paris refused to accede to the American demands.40 Thomas Jefferson himself said that “[t]he day that France takes possession of New Orleans […] seals the union of two nations who in conjunction can maintain exclusive possession of the ocean. From that moment we must marry ourselves to the British fleet and nation.”41 However, the Americans knew that given the French difficulties to take Saint-Domingue back from the rebels combined with the looming war with the British, Napoleon would be willing to negotiate.42 And they were right. As a matter of fact, they would be met with an offer that they could not have possibly imagined: the whole territory of Louisiana.43

(Natural Earth and Portland State University, Wikimedia)

The offer came after careful consideration by Napoleon. He had concluded that Louisiana was essentially a source of problems. The colony was in and of itself of little immediate value other than geostrategically – but even then, it was deemed undefendable for now: “I am thinking of ceding [Louisiana] to the United States. […] [The Americans] only ask from me one city in Louisiana; but I already consider the colony entire lost, and I think that in the hands of this nascent power it will be more useful to the politics, and even the trade of France, than if I attempted to keep it.”44 Consequently, Napoleon decided to sell this territory to the Americans. Louisiana had become a liability.

Furthermore, he did not want to frustrate the United States, whom he thought could become a rival of the United Kingdom if he sold Louisiana to them.45 Napoleon’s own words illustrate his train of thought: “To free the peoples from the commercial tyranny of England, she must be counterpoised by a maritime power who becomes her rival one day: these are the United States.”46 He also said: “I shall not keep a possession which would not be safe in our hands, which might create dissensions with the Americans, or would put me on bad terms with them. I shall use it, on the contrary, to attach them to me, to put them at odds with the English, and I shall create for the latter enemies who will avenge us one day, if we do not succeed in avenging ourselves.”47

Therefore, by selling Louisiana, Napoleon could have a favorable relationship with the United States while at the same time hoping they would become a maritime power capable of challenging the British. This also prevented the United Kingdom from occupying Louisiana, hence acquiring new territory in the Western hemisphere.48

While Spain had signed the treaty giving Louisiana back to France in 1800, the regime transfer came in effect only on November 30, 1803. The ceremony transferring authority from the French to the Americans would occur on December 20 of the same year, a bit less than 8 months after the purchase was concluded.49 Louisiana had officially been French again for only three weeks and was now American.50

(Wikimedia)

Was Louisiana Sold for Cheap?

Louisiana was sold for 80 million francs (15 million dollars), of which 20 million (3.75 million dollars) were retained by the American government as compensation for the actions of French privateers during the Quasi-War, as convened by the Treaty of Mortefontaine of 1800.51 Therefore, the colony was effectively sold for 60 million francs (11.25 million dollars).52 Given the vastness of the territory – more than 2 million square kilometers (approximately 1,243,000 square miles) – such a price could seem low.53

However, it would be wrong to assume that Louisiana was sold for cheap. Back then, and as already stated, the colony was little more than a loose zone of influence. It was immense, but barely exploited or populated. As an illustration, when it was ceded to the United States, there were approximately 50,000 inhabitants (excluding Native Americans and slaves of African origins),54 and during the French period (1682-1763), there were no more than 1,700 Native American slaves, while there were about 6,500 African slaves.55 The relatively low number of slaves indicates the lack of economic interests – or will to develop them – in the colony. Furthermore, around 1763, New Orleans, which was the only settlement that could qualify as an actual town, only hosted about 3,200 inhabitants.56 Therefore, when Louisiana was sold, there was approximately less than 0.03 colonist per square kilometer (or approximately 0.04 colonist per square mile). Napoleon was perfectly aware of this fact: he is reported to have said that Louisiana was “populated by rattlesnakes, coyotes and Sioux.”57

In truth, Louisiana had never been a priority of the French colonial policy. Its inhabitants had switched hands between France and Spain, and were a mix of descendants of the first French colonists, Acadians (who would become Cajuns), refugees from Saint-Domingue, free “people of color,” African slaves, Native Americans, and Spaniards. The locals had not forgotten France, but French patriotism had progressively declined.58 François Barbé-Marbois considered that even if France kept Louisiana and that the colony became successful, there would eventually be a risk of independence: “Those colonists have lost the memory of being French.”59 In a sense, he was right: they were, in a way, “Louisianan patriots.” They were more attached to the land itself than to the colonial power owning it.60

Consequently, Napoleon was not selling a profitable colony, and Louisiana as a whole had no direct use for France at the time. Moreover, as he stated himself, he decided to sell it while it was not even officially back in French hands: “Barely could I say that I cede [Louisiana] to [the Americans], since it is not in our possession yet.”61 As already mentioned, the colony would effectively be French again only for three weeks. Therefore, Napoleon essentially received money for a territory which was not even being administered by his government.

Finally, the price itself was not inconsequential. 60 million francs represented six years of the budget of the Ministry of the Navy and the Colonies, which was at the time the second most important budget of the French state.62 Additionally, the sum was meant to fund the construction of a military camp in Boulogne to prepare a landing in England.63

Conclusion

The Louisiana Purchase constitutes a dramatic event in the life of the United States that determinedly shaped the future of the country. As Robert Livingston stated: “We have lived long, but this is the noblest work of our whole lives. The treaty which we have just signed […] will change vast solitudes into flourishing districts. From this day the United States take their place among the powers of first rank.”64 It also constitutes one of the great events bonding France and the United States, along with the War of Independence, the gifting of the Statue of Liberty, and both World Wars.

The memory of French Louisiana still persists to this day, consciously or not. What used to be an immense single piece of land became divided into 15 different states. Only one of them kept the name Louisiana. It is still associated with French culture and a French past. The name itself is intrinsically attached to French history: Louisiana was named after French King Louis XIV.65 Whether they know it or not, the people of Louisiana have a historical bond with France. As Napoleon stated during the negotiation of the treaty: “May the Louisianans know that we only separate from them with regret […] that in the future, happy in their independence, they remember they were French […] so may they conserve for us feelings of affection, and may the common origin, the kinship, the language, the mores, perpetuate friendship.”66

- Gilles Havard, Cécile Vidal, Histoire de l’Amérique française, Paris: Flammarion, 2003-2019, 707.

- Ibid., 699; Bernard Gainot, L’Empire colonial français de Richelieu à Napoléon, Malakoff: Armand Colin, 2015, 181.

- Gainot, L’Empire colonial, 94; Marcel Dorigny, Jean-François Klein, Jean-Pierre Peyroulou, Pierre Singaravélou, Marie-Albane de Suremain, Grand Atlas des empires coloniaux : Des premières colonisations aux décolonisations, XVe-XXIe siècle, Paris: Autrement, 2015-2019,65, 88; Pierre Pluchon, Histoire de la colonisation française : Le Premier empire colonial (des origines à la Restauration), Paris: Fayard, 1991, 1016, 1018, 1025.

- Dorigny et al., Grand Atlas, 65; Andrew Roberts, Napoleon: A Life, New York: Penguin Books, 2014-2015, 300.

- Pluchon, Histoire de la colonisation, 1018.

- Roberts, Napoleon, 300.

- Patrick Bouhet, “Une vraie vision stratégique derrière l’échec,” Guerres & Histoire no. 51 (2019),37; Havard, Vidal, Histoire de l’Amérique, 700; Gainot, L’Empire, 181.

- Carrie Gibson, Empire’s Crossroads: A New History of the Caribbean, London: Pan Books, 2014-2015, 154-55.

- Ibid.,154-73.

- Alexander Mikaberidze, Les Guerres napoléoniennes : Une histoire globale, trans. Thierry Piélat, Paris: Flammarion, 2020, 196-97 (published in English under the title The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History by Oxford University Press in 2020).

- Roberts, Napoleon, 300.

- Gibson, Empire’s Crossroads, 170-72; Gainot, L’Empire colonial,179-80.

- Mikaberidze, Les Guerres napoléoniennes, 204; Havard, Vidal, Histoire de l’Amérique, 709.

- Derek McKay, H.M. Scott, The Rise of the Great Powers: 1648-1815, Abingdon: Routledge, 1983-2014, 302; On the French side, the economy had been in disarray; people were weary of war; the long-standing royalist rebellion in Vendée was not quashed until 1800; the French forces were in a poor condition; and the Royal Navy continuously prevented a French invasion of Great Britain (Ibid., 299; 301). Furthermore, Napoleon had to deal with the mentioned domestic issues to secure his hold on his new-found power, which made peace necessary. (Ibid., 299) On the British side, the economic situation was rapidly worsening, especially since trade had been impacted by the war; the people’s will to fight was waning; and London had lost all its continental allies, effectively making a French defeat impossible. (Ibid., 301) In this context, the British government realized that it could do nothing to counter French power at the moment. The only thing it could do was gaining time in order to deal with the pressing domestic socio-economic issues, hoping at the same time that Austria, Russia and Prussia would eventually realize that Napoleonic France would perpetually threaten European security. (Mikaberidze, Les Guerres, 193)

- Roberts, Napoleon, 318.

- Ibid., 308.

- McKay, Scott, The Rise, 302.

- Ibid., 305. Preventing control of the territory approximately encompassing present-day Belgium and Netherlands by a strong power, along with preserving the “balance of power” in Europe were key elements of British foreign policy. London considered these essential to ensure its security.

- Ibid.; Roberts, Napoleon, 314-15; Mikaberidze, Les Guerres, 223-25.

- McKay, Scott, The Rise, 305; Roberts, Napoleon, 312-14; Mikaberidze, Les Guerres, 222-23; 223-24.

- Mikaberidze, Les Guerres, 195-96; 227; 228.

- Roberts, Napoleon, 319.

- Mikaberidze, Les Guerres, 221-34.

- Bouhet, “Une vraie vision,” 37.

- Pluchon, Histoire de la colonisation, 913.Leclerc was the general in charge of the Saint-Domingue expedition; Roberts, Napoleon, 325; Havard, Vidal, Histoire de l’Amérique, 707.

- Havard, Vidal, Histoire de l’Amérique, 709.

- Dorigny et al., Grand Atlas, 50-1.

- Pluchon, Histoire de la colonisation, 913.

- Roberts, Napoleon, 324.

- Havard, Vidal, Histoire de l’Amérique,658-59.

- Ibid.,699-700. The territory given back to France was not exactly the same as the one France used to possess. France did not get back the Louisianan part located east of the Mississippi River. (Havard, Vidal, Histoire de l’Amérique, 700, 703; Dorigny et al., Grand Atlas, see maps pages 51, 55, and 67)

- Ibid., 706.

- Ibid., 700; Mikaberidze, Les Guerres, 205.

- Mikaberidze, Les Guerres, 205.

- Ibid., 206.

- Ibid., 205.

- “From Thomas Jefferson to Robert R. Livingston, 18 April 1802,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-37-02-0220 (last accessed April 29, 2023).

- Gainot, L’Empire, 200-1.

- Mikaberidze, Les Guerres, 206; Havard, Vidal, Histoire de l’Amérique, 707.

- Ibid.; Michaël Garnier, “Louisiane,” in Dictionnaire Napoléon : I-Z, ed. Jean Tulard (Paris: Fayard, 1987-1999-2011), 223.

- “From Thomas Jefferson.”

- Havard, Vidal, Histoire de l’Amérique, 707.

- Ibid.

- Pluchon, Histoire de la colonisation, 913.

- Havard, Vidal, Histoire de l’Amérique, 709.

- Pluchon, Histoire de la colonisation, 913.

- Havard, Vidal, Histoire de l’Amérique, 709-10.

- Mikaberidze, Les Guerres, 206.

- Havard, Vidal, Histoire de l’Amérique, 711.

- Ibid., 712.

- Havard, Vidal, Histoire de l’Amérique, 707-8; Mikaberidze, Les Guerres, 207; Garnier, “Louisiane,” 223.

- Mikaberidze, Les Guerres, 207.

- Ibid.

- Havard, Vidal, Histoire de l’Amérique, 712.

- Dorigny et al., Grand Atlas, 51.

- Ibid.

- Gainot, L’Empire, 181.

- Havard, Vidal, Histoire de l’Amérique, 686-87. On Cajun identity, see ibid., 692-95.

- Ibid., 710.

- Havard, Vidal, Histoire de l’Amérique, 687.

- Pluchon, Histoire de la colonisation, 913.

- Bouhet, “Une vraie vision,” 37.

- Gainot, L’Empire, 181.

- Roberts, Napoleon, 326.

- Havard, Vidal, Histoire de l’Amérique,104.

- M. Barbé-Marbois, “Histoire de la Louisiane, et de la cession de cette colonie aux États-Unis de l’Amérique septentrionale,” Journal des sciences militaires des armées de terre et de mer 19 (1830), 71.