This article was originally published by The Strategy Bridge.

Edit: Slightly cropped by blog owner

License

Introduction

It is widely agreed that there are three levels of war. From the more general to the more local, they are the strategic, operational, and tactical levels. Strategy is the alignment of means and ways to accomplish a political end. Strategy is about winning the war. Tactics consist of locally achieving victory through a series of actions that, taken globally, participate directly or indirectly in the accomplishment of strategy. Tactics are typically about winning battles. Finally, operations consist of connecting the tactics to the strategy. To do so, the operational level aims to create campaigns—a series of tactical actions which pursue specific operational aims—to ultimately accomplish specific strategic goals. The operational level is typically about winning a series of campaigns to accomplish the stated strategy.

Each level of war is essential to achieve success, and are all equally important. The Ludendorff Offensives of 1918 provide an illustration of why the operational level is essential. This article will provide the strategic context before presenting the objectives of the German campaign, its execution, and an analysis followed by a conclusion.

Strategic Context

On March 3rd, 1918, Russia officially withdrew from the Great War. Soon after, Romania followed.[1] Germany saw the withdrawal of these two states, notably the former, as an opportunity to take on both the French and British armies on more equal terms, and to relieve hardship on the home front.[2] Quartermaster General Erich Ludendorff, who was in charge of the German forces, wanted to strike a blow as early as possible to achieve decisive victory.[3] The entrance of the United States into the war provided manpower and supplies Germany could not match, and neither Germany nor its allies would stand the strain of a continued defensive war.[4] The German Supreme Army Command believed that only the breaking of the Entente would lead to victory.[5]

Objectives

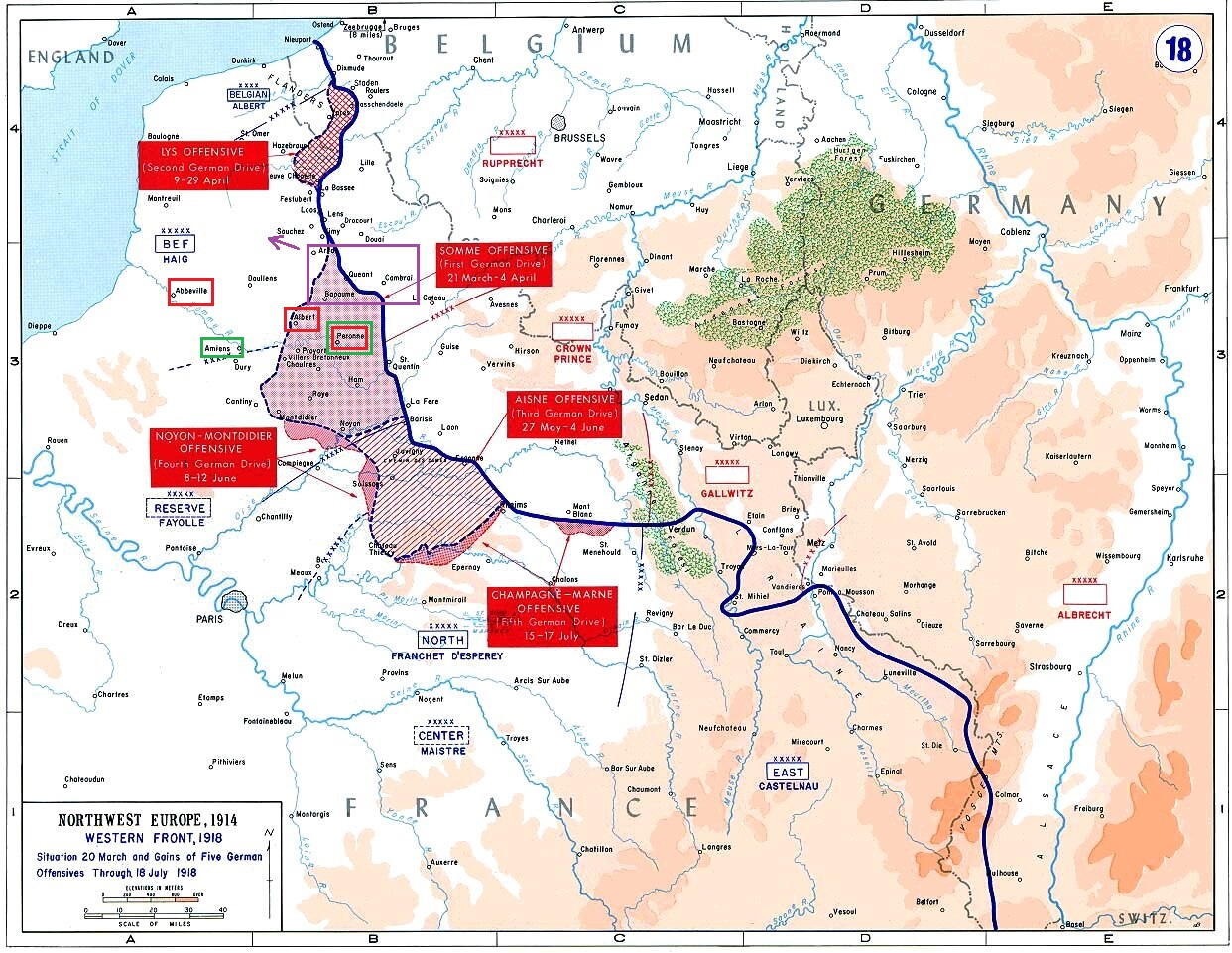

To break the Entente, Ludendorff wanted a swift, single campaign specifically targeting the British forces in the West before the American arrival.[6] The overall strategic objective was simple. The Germans were to punch through the British defense between Arras and the Oise river, then wheel north and envelop the British line, to allow for a push which would bring the defenders against the Channel ports and destroy them.[7] Specifically, a successful attack through the Péronne-Albert-Abbeville axis might separate the British from the French and crowd them into the sea.[8]

To do so, Ludendorff initially had three armies at his disposal: the 17th in the north, the 2nd in the center, and the 18th in the south.[9] The 2nd and 17th Armies first had to go southwest to clear the Cambrai salient, and then redirect in mid-battle to go northwest towards Arras and Vimy.[10] Specifically, the 2nd had to reach Péronne and then Amiens, while the 17th had to breach between Arras and Cambrai, then reach Bapaume and go north towards Saint-Pol.[11] The 18th essentially only had to protect the southern flank from the French.[12] The operational plan was designed to allow the Germans to breach the British lines quickly and envelop them before a potential counterattack.[13]

Added by article author: The red squares enclosing cities designate the overall German operational objectives (the Péronne-Albert-Abbeville axis).

The green squares designate the objectives of the 2nd Army.

The purple square designates the objectives of the 17th Army. The purple arrow represents the general direction toward which the 17th Army is meant to go upon completion of its initial objectives.

As can be noticed, the German assaults overall targeted areas which were not part of the initial operational and strategic objectives.

The British were the target for several reasons. The Germans believed the French would be too resilient, and that the British were more likely to give up ground not their own.[14] They also thought the end of British support would lead to French collapse.[15] The Germans considered the former to be tactically weaker than the latter, and that overall British readiness was diminished by instability in force structure, training, and over-extension of their lines.[16]

Execution of the Campaign

The whole campaign was subdivided in several operations from March to July 1918. The first was operation Michael, which started on March 21st. The attack in the south was very successful, while the northern attack not as much. Consequently, the critical operational objective, making for the coast via Péronne-Albert-Abbeville, was changed. The weight of the attack was shifted south to the 2nd and 18th Armies with Amiens as their objective, which they failed to achieve.[17]

From this moment, the original plan became the object of changes in an attempt to adapt to each situation. Ludendorff concluded that a further offensive against the British north of Péronne would be carried out on a too narrow front. As early as the evening of March 21st, the Germans made tactical changes that differed from the previously agreed positions, and Ludendorff moved divisions of the General Reserve not to the front, where the objective lay, but down south to the 18th Army’s sector, where the tactical soft spot was found. On March 23rd, the orders of the German Supreme Army Command pointed to a change of the attack axis to the south. Consequently, while the objective remained the same, the tactical disposition changed greatly.[18]

Regardless, the first offensive was a great tactical success. It produced the most significant territorial advances in the West since 1914, and in one day, the attackers captured a 300 kilometer-square of fortified area, a first on the western front.[19] Between March 24th and 26th, the Entente forces lost almost 10 kilometers per day, and on the 27th, the attackers pushed back the French by 15 kilometers and captured Montdidier.[20] The Germans gained almost 65 kilometers and threatened the vital railway junction of Amiens.[21] However, the final direction of Michael did not allow for the decisive envelopment initially sought. Moreover, the 17th and 2nd Armies could not enlarge the front with their exhausted forces.[22] The offensive was a tactical success, but achieved none of the stated operational or strategic aims.

The German offensives over the next four months would also achieve overall tactical success with significant territorial gains. However, they would achieve no real operational or strategic goals. Yet Ludendorff kept attacking, as he wanted to keep the initiative and get a decision.[23] After several months of offensives, the strategic objective of defeating the British was not reached.[24] Ludendorff left his troops in a massive salient exposed on all fronts, refusing to order a retreat. They became the object of increasingly destructive blows.[25]

The Entente suffered more casualties than the Germans, but they had more available reinforcements and a strong industrial backing.[26] These factors, among others, enabled the Entente to take hard hits from the Germans before decisively counterattacking. The German forces were now fragile, and its best soldiers had been lost in the offensives.[27] All of their following operations became attempts to maintain an unbroken front or to conduct an orderly retreat.[28] The Germans lost the initiative, and would never regain it.[29]

Analysis

The German offensives of March-July 1918 demonstrated the German ability to achieve great tactical success. By mid-July 1918, the territory controlled by the German Empire stood at its greatest ever extent, coming close to Paris.[30] However, the offensives were an utter operational and strategic failure. One of the main reasons is the inability of Ludendorff to follow the stated operational aims.

Indeed, Ludendorff ordered assaults that did not serve the initial operational and strategic objectives, objectives he lost sight of. He dissipated his forces in a series of attacks that achieved tactical success, but no operational or strategic decision.[31] He did so despite knowing he had only enough forces for one frontal assault.[32]

While the strategic and operational objectives were clear, Ludendorff got carried away by tactical successes and obsessively wanted to exploit local breakthroughs. He laid more stress on the question of successful tactics than on the strategic objects to be achieved. Ludendorff stated a strategic plan that ignored the tactical factor will fail, and that without tactical success strategic objectives cannot be achieved.[33] While axiomatic, it does not mean the tactical aspect must prevail. It must be equally considered with the strategic and operational aspects.

By overly focusing on the tactical level, he failed to articulate tactical objectives which were coherent with the operational objectives. Ludendorff argued that it was enough to punch a hole and that the rest would follow.[34] Instead of keeping in mind the whole purpose of the campaign, he kept adapting the plan according to local circumstances and events, often on a daily basis.[35] Such a method could, in theory, absolutely be relevant depending on the situation. However, the plan must always keep in mind the general purpose of the campaign and the nature of the faced adversary.[36] Ludendorff failed to do so.

For instance, between March 28th and April 6th, the Germans lost time and means that could have benefitted the bigger operation against the British in the north—the real object of the German campaign—by stubbornly attacking other locations.[37] Moreover, he decided to attack on the Chemin des Dames, where no tactical breakthrough could have broken up the French troops, the bulk of which were still fresh. Instead, he should have focused on the capture of Amiens or Abbeville, which were the only decisive objectives within possible reach, since their occupation could have split the French and the British.[38]

In late May, Ludendorff took the decision to suspend the offensive in Flanders and to send all his forces to Champagne, in part to threaten Paris.[39] While such a target was surely tempting, this move did not pursue the initially stated operational and strategic aims of the whole campaign. The Germans even tried to enlarge their zone in Champagne, though it meant postponing further attacks against the British and giving them and the Americans time to strengthen.[40] Again, Ludendorff failed to follow the initially stated operational and strategic objectives.

Ignoring the operational aims of Michael also had subsequent, negative consequences for the next major step of the German plan. Indeed, operation Georgette was launched by Ludendorff on March 28th despite the fact the initial operational goals had not been accomplished.[41] Its objectives were to weaken the British forces and to force them to fall back to Calais, and to take at least the transportation nodes of Hazebrouck and if possible of Saint-Omer.[42] However, Michael had failed to sufficiently weaken the British, and most importantly failed to draw their reserves to the south.[43] But the Germans decided to start Georgette anyway, as there was no other alternative.[44]

Ludendorff also failed to acknowledge that the Entente had superior manpower and supplies, a good logistical system, and was fighting as a single coordinated force.[45] Consequently, his operationally and strategically useless offensives had even less chances of being anything more than tactically successful.

The German campaign planned for a series of sufficiently quick attacks between Picardy and Flanders in a sufficiently wide area to disrupt the maneuver of the British reserves. These attacks also had to be powerful enough to take the transportation nodes of Amiens, Saint-Pol, Hazebrouck, and if possible of Abbeville and Saint-Omer.[46] But the series of decisions taken by Ludendorff, based on tactical opportunities, rendered this plan moot. He attacked secondary locations and objectives which did not serve the initially stated operational and strategic aims, when he should have focused all his forces on the main campaign goals to even have a chance of obtaining any positive strategic effect.

Conclusion

Of course, the sole failure to follow the initially stated operational aims does not explain entirely the German failure in 1918. The Germans were unable to mount more than one offensive at a time, meaning the Entente could more easily organize its forces to face the German offensives.[47] The Entente also eventually devised means to better face the powerful German assaults after learning how they worked. Its soldiers and leaders also naturally deserve credit for being able to organize effective defenses and counterattacks. Finally, the German strategy, even if the operational aims had been fulfilled, may very well not have succeeded anyway, given the strategic context in 1918 and because of flaws in the German strategy and campaign plan.[48] However, one thing is certain: failing to follow the operational aims crushed any chance of success. Tactical excellence could not compensate for this flaw.

[1] Hew Strachan, The First World War, New York: Viking Penguin, 2004, 270.

[2] William Philpott, War of Attrition: Fighting the First World War, New York: The Overlook Press, 2014, 305.

[3] Strachan, The First World War, 291.

[4] Major Patrick T. Stackpole, German Tactics in the “Michael” Offensive – March 1918, Pickle Partners Publishing, 2014, Chapter 1 – Introduction, Kindle; Lieutenant-Colonel Philip Neame, German Strategy in the Great War, London: Edward Arnold & Co., 1923, 102.

[5] Stackpole, German Tactics, Chapter 1 – Introduction.

[6] Pierre Jardin, “Ludendorff, le tacticien dépassé par la stratégie,” Guerres & Histoire, no. 33 (October 2016), 83; Stackpole, German Tactics, Chapter 1 – Introduction; Timothy T. Lupfer, “The Dynamics of Doctrine: The Changes in German Tactical Doctrine During the First World War,” Leavenworth Papers no. 4 (July 1981), 37; Neame, German Strategy, 102.

[7] Stackpole, German Tactics, Chapter 4 – Analysis of the Offensive – German Plan and Task Organization.

[8] Neame, German Strategy, 103.

[9] Stackpole, German Tactics, Chapter 4 – Analysis of the Offensive – German Plan and Task Organization.

[10] Neame, German Strategy, 107.

[11] Michel Goya, Les vainqueurs : Comment la France a gagné la Grande Guerre, Paris: Editions Tallandier, 2018, 111.

[12] Neame, German Strategy, 107.

[13] Stackpole, German Tactics, Chapter 4 – Analysis of the Offensive – German Plan and Task Organization.

[14] Ibid., Chapter 1 – Introduction; Strachan, The First World War, 293.

[15] Stackpole, German Tactics, Chapter 1 – Introduction.

[16] Ibid., Chapter 3 – Preparation of the Offensive – The British Defense.

[17] Neame, German Strategy, 107.

[18] Ibid., 107-8.

[19] Strachan, The First World War, 296; Goya, Les vainqueurs, 135-36.

[20] Goya, Les vainqueurs, 120, 123.

[21] Strachan, The First World War, 296.

[22] Jardin, “Ludendorff,” 84.

[23] Strachan, The First World War, 297.

[24] Goya, Les vainqueurs, 196.

[25] Jardin, “Ludendorff,” 84.

[26] Goya, Les vainqueurs, 170.

[27] Ibid., 187.

[28] Neame, German Strategy, 115.

[29] Ibid., 114.

[30] Strachan, The First World War, 298.

[31] Jonathan M. House, Combined Arms Warfare in the Twentieth Century, Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2001, 55.

[32] Jardin, “Ludendorff,” 84.

[33] Neame, German Strategy, 103.

[34] Philpott, War, 312.

[35] Ibid., 313.

[36] Ludendorff behaved on the western front as he did in Russia, and assumed that the German methods used in the east would be as efficient in France against different enemies (Strachan, The First World War, 293).

[37] Goya, Les vainqueurs, 125.

[38] Neame, German Strategy, 112.

[39] Goya, Les vainqueurs, 158.

[40] Ibid., 164.

[41] Ibid., 127.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid., 128.

[44] Ibid., 127.

[45] Philpott, War, 322.

[46] Goya, Les vainqueurs, 136-37.

[47] Ibid., 188.

[48] Specifically, temporarily knocking out one belligerent would most likely not prove decisive–as shown in Poland in 1915, Romania in 1916 and Italy in 1917–especially at this stage of the war (Philpott, War, 312). Moreover, the German tactics and operations would be effective against thin lines supported by poor logistics, but they would likely not be optimal against the very effective logistics, deep defenses, and large manpower of the Entente (Ibid., 313). Additionally, considerable German combat power was wasted on the defensive mission of the 18th Army. Indeed, the 18th was augmented, instead of the 2nd and in particular the 17th, although they had to accomplish the critical effort (Stackpole, German Tactics, Chapter 4—Analysis of the Offensive—German Plan and Task Organization). Finally, the Germans failed to acknowledge the impact of the Entente reserves which could be poured into battle. The Entente had enough reserves to contain offensives against Amiens, and soon after the start of Michael, the coalition had nearly 60 divisions in reserve supported by excellent road and rail communications. Therefore, however successful the operation, it was almost certain the Entente reserves could have reached the battlefield in time to prevent a critical breakthrough (Philpott, War, 312; Neame, German Strategy, 109).